And how to read them without overestimating—or underusing—their influence

The trigger for this blog post came from a conversation last month with a PhD student working on a thesis on foreign direct investment. During the interview, he asked a question that was simple on the surface but difficult to answer cleanly: what role do consultancy reports actually play in FDI decisions?

Not policy. Not incentives. Not site visits.

Reports.

In practice, these documents appear everywhere in the FDI ecosystem, yet we rarely examine their role directly.

Over the years, while working closely with investment promotion agencies, I’ve collaborated with a wide range of consulting firms—from the Big Four to highly specialised, country- and sector-focused advisors. I’ve seen their reports circulate quietly: referenced in board presentations, quoted in IPA pitch decks, skimmed by senior executives, and archived by analysts. Rarely read end to end, yet consistently influential.

This post is an attempt to shed some light on that layer of the FDI process: how they are produced, why they carry weight, where their limits lie, and how they shape global investment conversations long before capital actually moves.

What consultancy reports actually influence

Consultancy reports rarely trigger an investment decision. What they influence is whether a country or sector enters the conversation at all.

In board and strategy discussions, they are often used to:

- validate early interest (“others are seeing this too”)

- frame risk and opportunity in familiar language

- compare markets quickly using standardised lenses

Once a market is framed as “plausible,” teams are allowed to explore it further. That is the real impact.

Europe–India examples where reports shifted perception

Electronics manufacturing

For a long time, India barely featured in European electronics discussions outside IT services. That began to change when consulting firms started publishing sustained analysis on China+1 strategies, supply-chain concentration risk, and electronics value-chain diversification.

What mattered wasn’t any single policy or incentive. It was comparison. When India started appearing alongside Vietnam, Mexico, and Eastern Europe—using the same analytical frameworks—it became easier for European firms to evaluate trade-offs rationally. In many cases, this led first to supplier conversations, pilot manufacturing, or sourcing offices. Capital commitments followed later.

Global Capability Centres (GCCs)

India has hosted captive centres for decades, but the narrative shifted when consultancy reports reframed them as strategic capability hubs rather than cost centres. Engineering, cybersecurity, analytics, product development—these functions began to feature prominently in GCC analyses.

For many European mid-sized companies, this reframing was critical. What might have been rejected internally as “outsourcing” became acceptable as “talent strategy” or “resilience planning.” Often, the initial approval wasn’t labelled as FDI at all. The investment structure came later.

Green manufacturing and energy transition

As Europe pushes toward decarbonisation, consulting reports on green hydrogen, batteries, and renewable-linked manufacturing have increasingly included India as a plausible part of the solution. These narratives help companies reconcile sustainability commitments with cost and scale—an increasingly central tension in capital allocation decisions.

Again, the outcome is rarely immediate large-scale FDI. More often, it starts with joint ventures, technology pilots, or small manufacturing footprints aligned with renewable energy corridors.

How these reports are actually produced

Understanding their influence requires understanding how they are made.

Most large consultancy reports draw from four main inputs.

First, client work. Years of advising corporates, governments, and investors generate privileged insight into real projects—what scaled, what stalled, and what surprised decision-makers. This experience often shapes conclusions more than publicly visible data.

Second, public and quasi-public datasets: World Bank, UNCTAD, OECD, national statistics, trade flows, patent filings, logistics indicators, and increasingly, talent data. The value lies in synthesis rather than originality.

Third, primary research: executive surveys, expert interviews, and roundtables. These inputs capture sentiment and intent rather than prediction—but sentiment often drives early-stage FDI decisions.

Fourth, proprietary models and benchmarks. Consulting firms maintain internal frameworks to compare markets across cost, talent depth, infrastructure, policy stability, and scalability. Shifts in a country’s positioning usually reflect changes in these assumptions.

Why consultancies publish these reports

Partly, the motivation is obvious: thought leadership builds brand relevance and future advisory pipelines.

But there is also a practical internal function. These reports help firms align their own worldview. They ensure consultants across geographies speak the same strategic language when clients ask, “Should we be looking at this market now?”

In that sense, reports are not just external communication tools. They are internal coordination mechanisms.

Are these reports neutral?

Not entirely.

They are shaped by client demand, prevailing narratives, and what can be benchmarked across countries. Optimism is common. Practical challenges—such as regulatory timelines, land access, partner quality, and on-the-ground execution—receive far less attention.

At the same time, when several firms independently highlight the same trend, it usually reflects something real happening beneath the surface.

The mistake is not using these reports. The mistake is treating them as complete answers.

The reality: we hoard these reports, but rarely read them

There’s also an uncomfortable truth.

Most consultancy reports are long. Dense. Data-heavy. They arrive in inboxes, get downloaded, bookmarked, and quietly archived. We tell ourselves we’ll read them properly later.

We usually don’t.

Instead, we skim executive summaries. We glance at a few charts. A handful of phrases stick—“China+1,” “capability hubs,” “energy transition.” Those phrases then circulate through meetings, slides, and internal memos. The report is technically unread, but its ideas travel.

In that sense, these documents function less like books and more like signal carriers. Their real influence lies not in the tables, but in the vocabulary they normalise.

Perhaps that’s how they are meant to be used.

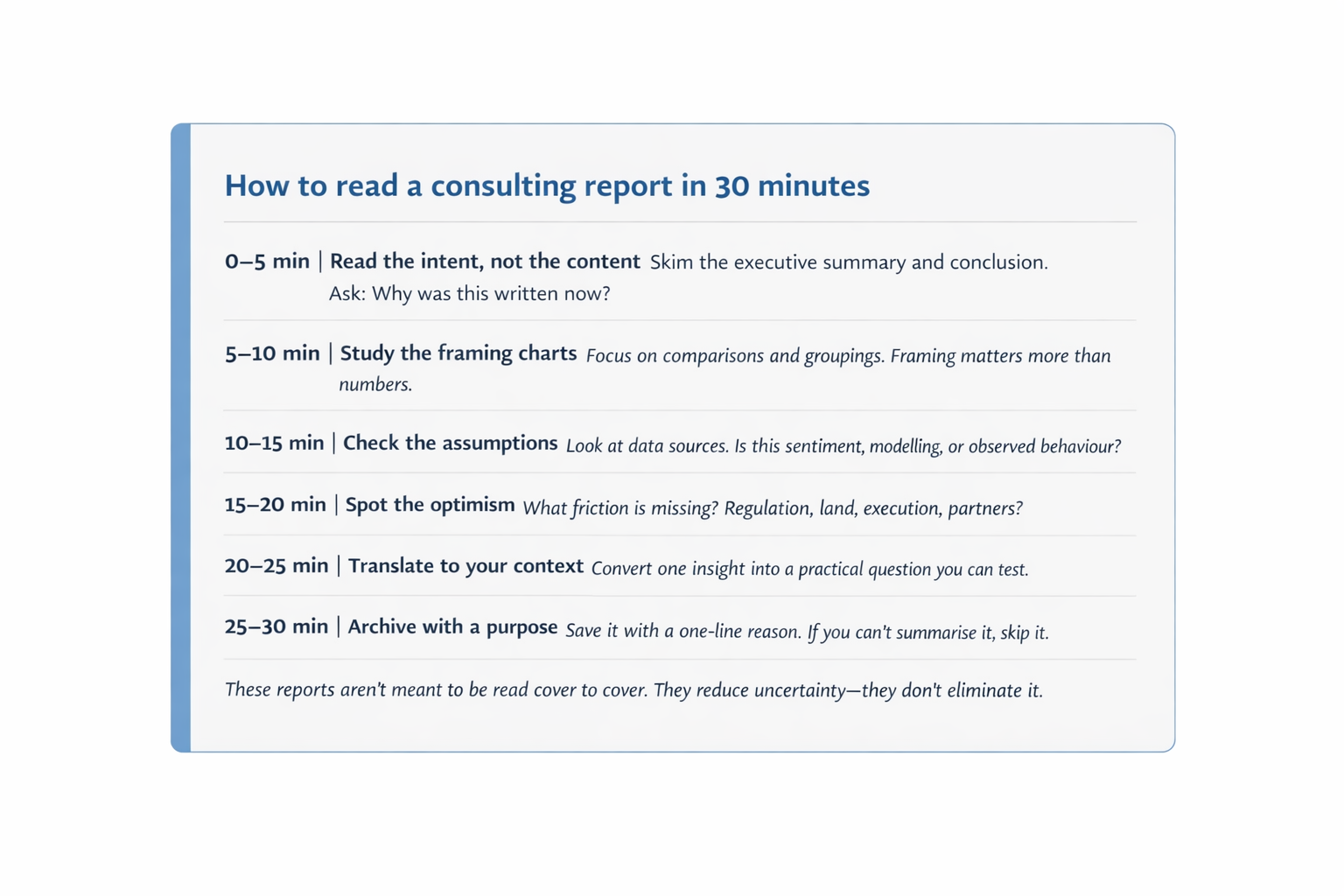

How to read a consulting report in 30 minutes

The most effective way to use these reports is not to read them end to end, but to extract framing, question assumptions, and test relevance against reality. Done well, that takes about half an hour.

The quiet role consultancy intelligence plays in FDI

FDI doesn’t move because of a PDF.

It moves because people inside organisations slowly become comfortable with uncertainty. Consultancy reports help that process along. They turn vague interest into structured curiosity. They move conversations from “Should we look at this market?” to “How do we test it?”

In cross-border investment, that shift is often the hardest step.

And that is why these reports—imperfect, biased, but influential—deserve closer attention.